When School's Out, Hunger Doesn't Take a Summer Break

5 decades of Summer Meal Programs—and Why This Summer's Setbacks Should Alarm Us All

As the 2025 school year begins and children across America return to classrooms, I wanted to take a step back and look at a summer-time program that looked a little different this year. Fewer children had access to summer meal programs than in recent years and the infrastructure that took decades to build is beginning to fray. Reports from across the country document the same pattern. Fewer sites, reduced hours, and communities unable to offer the summer nutrition programs that have become essential infrastructure over the past five decades.

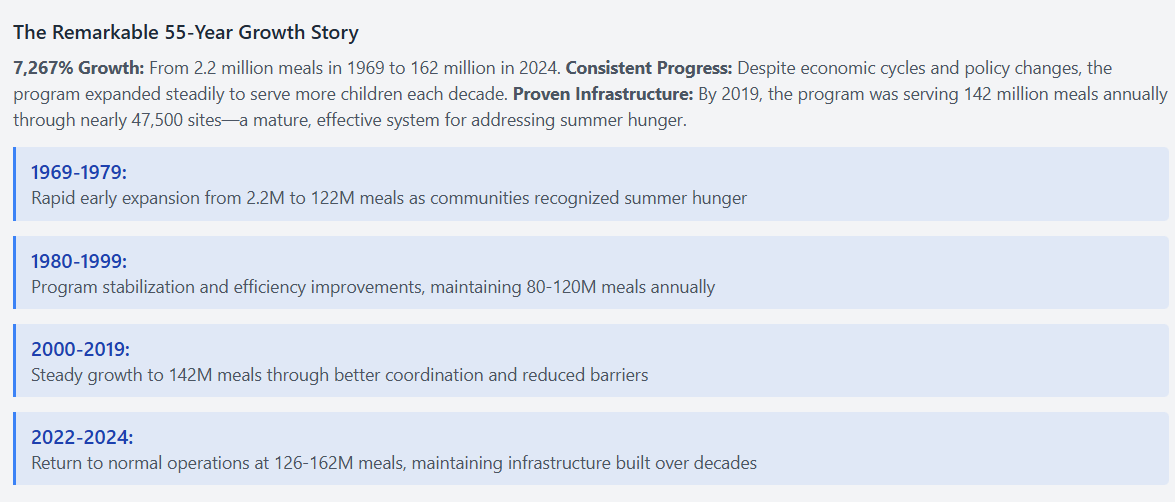

For 55 years, the Summer Food Service Program has grown from a modest initiative serving 99,000 children to a comprehensive network that typically reaches over 2.7 million children daily. Yet this summer may have marked a concerning departure from that trajectory of steady growth and improvement.

The data tells a story of amazing success followed by worrying retreat. From about 1980 to 2019, the program experienced consistent growth, expanding from 1,200 sites serving 2.2 million meals over an entire summer to nearly 47,500 sites delivering 142 million meals annually. But summer 2025 saw some declines in program availability, with early reports suggesting fewer sites operated compared to previous years.

Five Decades of Steady Progress

The numbers show substantial institutional development and expanding reach. In 1969, the Summer Food Service Program operated from just 1,200 sites, serving fewer than 100,000 children. By 2019, before the pandemic disrupted normal operations, the program had grown to 47,471 sites serving 2.7 million children and delivering nearly 142 million meals. This was a 6,345% increase in total meals served over five decades.

The program's expansion reflects policy development and growing recognition of summer hunger as a serious challenge for American families. The 1970s brought rapid expansion as communities and policymakers recognized that child nutrition didn't pause when school ended. Sites increased from 1,200 in 1969 to 23,700 by 1977, while participation grew to serve 2.8 million children, really similar to current levels.

The program weathered challenges during the 1980s and 1990s as federal priorities shifted, but emerged stronger with improved targeting and administrative efficiency. The introduction of direct certification and coordination with school meal programs helped reduce barriers while ensuring resources reached families who needed them most.

The 2000s and 2010s saw steady, sustainable growth. By 2010, the program was serving 2.3 million children through 38,000 sites. By 2019, participation had grown to 2.7 million children served through 47,471 sites, representing a strong, effective system for addressing summer hunger that had achieved greater scale and reach.

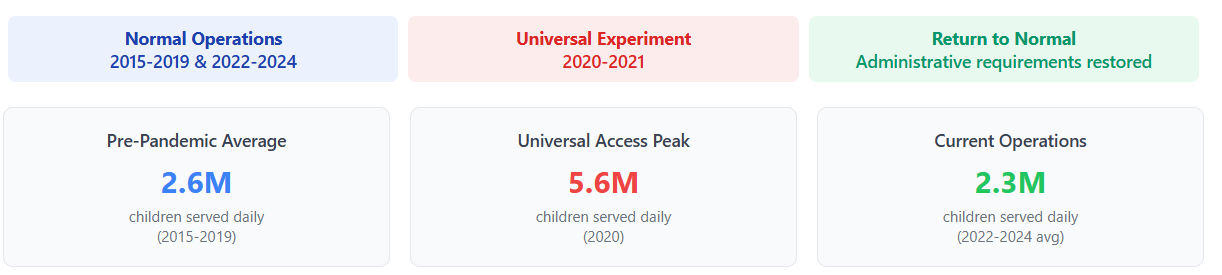

The COVID-Era Experiment

The pandemic years of 2020-2021 deserve attention not as a baseline for comparison, but as evidence of what becomes possible when administrative barriers disappear and federal support dramatically expands. Peak participation reached 5.6 million children in 2020 and 5.1 million in 2021, while total meals served peaked at over 3 billion in 2021.

Peer-reviewed studies demonstrate improvements in food security with summer meals participation, and summer nutrition programs are an important strategy for preventing learning loss among school-aged children.

More importantly, the COVID expansion revealed the true scope of summer hunger in America. When universal access became available, participation increased by 300-400% in many communities. This suggests that the steady participation levels of 2.5-2.7 million children that the program had achieved by 2019 likely represented effective programming within existing constraints, but significant unmet need remained.

Return to Normal—And Then Decline

The 2022-2024 period saw the program return to more typical operations as emergency waivers expired. Participation in 2022 settled at 2.7 million children through 36,382 sites, actually slightly higher than 2019 levels despite reduced site availability. The 2023 and 2024 numbers showed continued operation in the normal range: 2.2 million and 2.8 million children respectively, served through approximately 36,000 sites.

This stabilization around 2.5-2.8 million participants shows a return to the program's pre-pandemic trajectory rather than a concerning decline. The reduction in sites from the 47,000+ levels of 2019 to around 36,000 in recent years reflects both operational adjustments after COVID and the reality that some communities found alternative ways to serve children.

What makes 2025 different, and alarming, is that this summer saw further reductions from even these normalized levels. Early reports suggest that fewer than 32,000 sites operated summer meal programs this year, the lowest number since the early 2010s. Communities that had operated summer meal sites for years were unable to continue due to funding constraints, staffing challenges, and increased administrative requirements.

This Summer's Warning Signs

While comprehensive 2025 data isn't yet available, early indicators suggest significant stress on summer meal program infrastructure. Communities across the country faced funding challenges, with Oakland initially deciding to cancel its summer food program entirely before reversing the decision to offer meals at fewer sites due to budget constraints.

The broader context reveals mounting pressure on food assistance programs. In March 2025, the USDA canceled $1 billion in funding for the Local Food Purchase Assistance Program and Local Foods for Schools Program, affecting more than 10,000 farms and reducing access to local foods for schools and food banks. While these programs are separate from summer meals, they indicate reduced federal commitment to child nutrition infrastructure.

Food costs have continued to increase, with food prices rising 2.9% in the 12 months ending July 2025, following years of significant inflation. Federal reimbursement rates for summer meals increased by 3.6% in 2025, but school nutrition professionals report that even regular school meal reimbursements fall short of actual costs, with the average cost of producing school meals exceeding federal per-meal reimbursements even before the pandemic.

The passage of the Budget Reconciliation Bill in July 2025 has created additional uncertainty around nutrition support programs, contributing to the challenging environment for organizations considering whether to sponsor summer meal sites. These converging pressures, rising costs, inadequate reimbursements, and policy uncertainty, threaten the infrastructure that took decades to build.

The True Stakes

Behind the statistics are real consequences for real children and families. Research consistently shows that food insecurity spikes during summer months when school meals aren't available. For the 22 million children who receive free or reduced-price school meals, summer represents a genuine nutritional crisis when those programs end.

The families affected aren't necessarily those who qualify for other assistance programs. Many working families earn too much to qualify for SNAP benefits but still struggle to replace the 10 meals per week per child that school breakfast and lunch programs provide. Summer meal programs serve as an important bridge, ensuring that children maintain access to adequate nutrition year-round.

When summer meal sites close or reduce operations, children don't simply find alternative sources of nutrition. Studies document measurable increases in emergency room visits for conditions related to food insecurity during summer months in communities that lack summer meal programs. Research shows that children without access to summer nutrition programs are more likely to experience learning loss and start the new school year behind their peers.

What the Story Teaches Us

The long-term trajectory of summer meal programs offers clear lessons about what works. From 1969 to 2019, consistent federal support and policy improvements drove steady growth in both participation and effectiveness. When administrative barriers were reduced—such as through direct certification and coordination with school programs—participation increased among eligible families.

The program's success over five decades demonstrates that summer meal programs represent sound public policy: they effectively reach families who need support, they operate efficiently when barriers are minimized, and they provide measurable benefits to participating children. The COVID-era expansion proved that even greater reach is possible when resources and political will align.

Most importantly, the data shows that progress isn't inevitable. The infrastructure that took 50 years to build can be eroded quickly when support wanes. This summer's reductions in site availability represent the first significant step backward in program capacity in over a decade. Hopefully we do not return to a backslide similar to what was experienced in the 80s.

The Path Forward

The steps needed to reverse this summer's troubling trends are straightforward: adequate federal funding, streamlined administrative processes, and recognition that summer hunger requires sustained attention.

Several specific steps could reverse this summer's troubling trends. Enhanced federal reimbursement rates could address the rising costs that forced many sponsors to withdraw from the program. Simplified administrative requirements could reduce barriers for community organizations while maintaining necessary oversight. Targeted support for rural and underserved communities could ensure that program reductions don't disproportionately affect children with the fewest alternatives.

State-level action offers another path forward. Just as several states have implemented universal school meal programs, states could enhance summer meal programs using state funding to fill gaps in federal support. Some states are already experimenting with summer grocery benefits and other innovative approaches to address summer hunger. But I think spending more on ensuring kids have access to food is something we can all agree on, even if it takes spending less on other things federally (you know, like national defense, ICE, etc…).

Looking Ahead

According to USDA data, 45 percent of households with children living near a summer meal site are food insecure, which is higher than the 14 percent of households with children who are food insecure nationally. The data shows that summer hunger is real and measurable, and that summer meal programs effectively address this challenge when adequately supported.

The economic costs of childhood food insecurity include increased healthcare expenses, reduced educational outcomes, and diminished long-term productivity. Beyond the economic calculus, there's a straightforward moral issue: children are going hungry during summer months in communities that have the capacity to provide adequate support.

The data shows what's possible with sustained commitment to feeding children year-round. Whether policymakers will build on that success or allow the infrastructure to erode through underfunding will determine outcomes for millions of children in summers ahead.

Data Source: USDA Food and Nutrition Service, Summer Food Service Program Annual Summary (FY 1969-2024)